Be Golden as gold mine & Green as leaf

carpe diemBe Golden as gold mine & Green as leaf

carpe diemgrunge

grunge

Grunge. It’s a word that became synonymous with the Seattle sound. It’s a word that was used to describe a number of different “alternative” bands from the region in 1980s, and then also into the 1990s with bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, Mudhoney and Screaming Trees. At one point, the term became so convoluted that the grunge label was used to describe bands like Candlebox, Stone Temple Pilots, Bush and Silverchair, bands that had little or nothing to do with the northwest music scene and bands the progenitors of grunge hated to be associated with.

But where did the term “grunge” come from? And why “grunge?” How did a word that basically was a synonym for dirt or grime become a descriptor of a new music genre?

The first noted instance of referring to a Seattle band as “grunge,” was in a 1981 letter by Mark Arm, according to Clark Humphrey in his account of the Seattle music scene, Loser.1 In his letter, in which he nominated his own “band”, Mr. Epp and the Calculations, as the most overrated band in Seattle, Arm writes: “I hate Mr. Epp and the Calculations! Pure grunge! Pure noise! Pure shit!” (Of course, Epp as a band didn't even exist yet.)

Bruce Pavitt later claimed to have popularized the term as a musical label in 1987, when he wrote some promotional copy for Green River, describing the band as “ultra-loose grunge that destroyed the morals of a generation”.2 Humphrey also notes that a Sub Pop press release described Mudhoney as “ultra sludge, glacial, heavy special, dirty punk.” It was among the many references Sub Pop would make toward “grunge” in its marketing, an exploitation they cheerfully fed to reporters and fans.

In the late 80s, “grunge” did actually define a sound – high levels of distortion, feedback, fuzz effects, a fusion of punk and metal influences. Though the bands attributed to the label definitely had unique talents, there was definitely a similar “sound” there. Much of this had to do with similar production and promotion. Many of these bands were on either the C/Z or Sub Pop record labels. Jack Endino, the so-called “Godfather of Grunge” recorded Soundgarden, Mudhoney, Green River, Nirvana and Blood Circus between 1984 and 1989.

But, by 1990, “grunge,” as a synonym for loud, heavy music, had peaked. Bands like Green River, the U-Men, Cat Butt, Feast and Blood Circus had broken up; Mudhoney and Soundgarden were veering into a new sound, and the scene was full of bands that didn’t fit the original label, like the Fastbacks, Young Fresh Fellows, Posies, Walkabouts and Beat Happening. (Even Nirvana, now liberated from the more restrictive sound requirements of Sub Pop, wanted to go into a poppier direction. Their more commercial approach was apparent in their breakthrough album, 1991’s Nevermind.) The 80s version of grunge, with long-haired musicians wailing away in front of tiny crowds at squalid clubs like the Central Tavern or Squid Row, was dead.

n 1991, Nirvana’s Nevermind album, Pearl Jam’s Ten, and Soundgarden’s Badmotorfinger were all released, and the following year, Alice in Chains released their landmark album, Dirt. With four huge alternative stars all hailing from the same region, the music media wanted a label to describe this new Seattle sound. Despite the music sounding significantly different from each other (and from bands that originally carried the "grunge" label), the “big four” Seattle bands were all labelled as grunge. Any other bands from Seattle at the time, were lumped into the category as well. Ben London of Alcohol Funnycar described it like this: “If you lived in Seattle and were under 30 at that point, you were grunge,” no matter what your band sounded like.

While inaccurate, the grunge label was convenient. For years, MTV and mainstream music magazines used grunge in almost every reference to Pearl Jam, Nirvana or Seattle music. The people directly involved with the music scene, however, hated the term. Former Rocket writer and Sub Pop staffer Jeff Gilbert said the word was like “talking to someone with bad breath: you could put up with it, you still wanted to distance yourself.” Ben Shepherd of Soundgarden put it a little more succinctly: “Grunge was a fucking word used in TV commercials about scum on your shower curtains.” Stone Gossard told an interviewer in the 90s that he refused to even say the word.

Usage of the “g-word” was reviled in Seattle; anyone who used it identified themselves as a poseur. The ridiculousness of the "grunge" label reached a peak when bands like Stone Temple Pilots and Bush were being lumped into the category as well.

Long-time Seattle scene followers even noted that this '90s definition of grunge was completely different than the '80s definition. Pearl Jam would have never been considered grunge compared to bands like the U-Men, Mudhoney or TAD. And it didn't stop there. As Everett True noted in Mark Yarm's Everybody Loves Our Town: An Oral History of Grunge, “the original grunge, the Sub Pop grunge, had nothing to do with the grunge that became popular, like Silverchair and Puddle of Mudd

espite the bands’ almost-universal hatred of this umbrella term, it stuck, even 20 years later. For example, two of the most prominent books on the Seattle/northwest music scene had "grunge" in the title: Greg Prato’s Grunge Is Dead and the subtitle of the aformentioned Mark Yarm oral history, Everybody Loves Our Town. The recent wave of 1990s nostalgia has brought more coverage on the "return of grunge" and its place in music history, especially as Nirvana became the first northwest band of the era to be enshrined in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Music fans who weren’t even alive in 1988 use grunge as an affectionate term for Pearl Jam and Nirvana.

So what was “grunge”? At the start, it was a joke. Then it became a simple description of a sound/attitude, as well as a Sub Pop hype promotional term. Ultimately, it became a quasi-genre of music based simply on bands’ Seattle origins. But whatever the meaning is, it’s clear that the term “grunge” has permanently linked those 80s and 90s northwest musicians in music history. A club, so to speak, of which they’ll have lifetime membership. Don’t expect the musicians to be proud, card-carrying members of this club, though.

“We never were grunge,” Shepherd insists.

“We were just a band from Seattle.”

.”

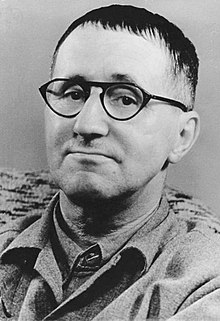

Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht, original name Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht, (born February 10, 1898, Augsburg, Germany—died August 14, 1956, East Berlin), German poet, playwright, and theatrical reformer whose epic theatre departed from the conventions of theatrical illusion and developed the drama as a social and ideological forum for leftist causes.

Until 1924 Brecht lived in Bavaria, where he was born, studied medicine (Munich, 1917–21), and served in an army hospital (1918). From this period date his first play, Baal (produced 1923); his first success, Trommeln in der Nacht (Kleist Preis, 1922; Drums in the Night); the poems and songs collected as Die Hauspostille (1927; A Manual of Piety, 1966), his first professional production (Edward II, 1924); and his admiration for Wedekind, Rimbaud, Villon, and Kipling

During this period he also developed a violently antibourgeois attitude that reflected his generation’s deep disappointment in the civilization that had come crashing down at the end of World War I. Among Brecht’s friends were members of the Dadaist group, who aimed at destroying what they condemned as the false standards of bourgeois art through derision and iconoclastic satire. The man who taught him the elements of Marxism in the late 1920s was Karl Korsch, an eminent Marxist theoretician who had been a Communist member of the Reichstag but had been expelled from the German Communist Party in 1926.

In Berlin (1924–33) he worked briefly for the directors Max Reinhardt and Erwin Piscator, but mainly with his own group of associates. With the composer Kurt Weill he wrote the satirical, successful ballad opera Die Dreigroschenoper (1928; The Threepenny Opera) and the opera Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (1930; Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny). He also wrote what he called “Lehr-stücke” (“exemplary plays”)—baldly didactic works for performance outside the orthodox theatre—to music by Weill, Hindemith, and Hanns Eisler. In these years he developed his theory of “epic theatre” and an austere form of irregular verse. He also became a Marxist.

In 1933 he went into exile—in Scandinavia (1933–41), mainly in Denmark, and then in the United States (1941–47), where he did some film work in Hollywood. In Germany his books were burned and his citizenship was withdrawn. He was cut off from the German theatre; but between 1937 and 1941 he wrote most of his great plays, his major theoretical essays and dialogues, and many of the poems collected as Svendborger Gedichte (1939). Between 1937 and 1939, he wrote, but did not complete, the novel Die Geschäfte des Herrn Julius Caesar (1957; The Business Affairs of Mr. Julius Caesar). It concerns a scholar researching a biography of Caesar several decades after his assassination.

The plays of Brecht’s exile years became famous in the author’s own and other productions: notable among them are Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (1941; Mother Courage and Her Children), a chronicle play of the Thirty Years’ War; Leben des Galilei (1943; The Life of Galileo); Der gute Mensch von Sezuan (1943; The Good Woman of Setzuan), a parable play set in prewar China; Der Aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui (1957; The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui), a parable play of Hitler’s rise to power set in prewar Chicago; Herr Puntila und sein Knecht Matti (1948; Herr Puntila and His Man Matti), a Volksstück (popular play) about a Finnish farmer who oscillates between churlish sobriety and drunken good humour; and The Caucasian Chalk Circle (first produced in English, 1948; Der kaukasische Kreidekreis, 1949), the story of a struggle for possession of a child between its highborn mother, who deserts it, and the servant girl who looks after it.

Brecht left the United States in 1947 after having had to give evidence before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He spent a year in Zürich, working mainly on Antigone-Modell 1948 (adapted from Hölderlin’s translation of Sophocles; produced 1948) and on his most important theoretical work, the Kleines Organon für das Theater (1949; “A Little Organum for the Theatre”). The essence of his theory of drama, as revealed in this work, is the idea that a truly Marxist drama must avoid the Aristotelian premise that the audience should be made to believe that what they are witnessing is happening here and now. For he saw that if the audience really felt that the emotions of heroes of the past—Oedipus, or Lear, or Hamlet—could equally have been their own reactions, then the Marxist idea that human nature is not constant but a result of changing historical conditions would automatically be invalidated. Brecht therefore argued that the theatre should not seek to make its audience believe in the presence of the characters on the stage—should not make it identify with them, but should rather follow the method of the epic poet’s art, which is to make the audience realize that what it sees on the stage is merely an account of past events that it should watch with critical detachment. Hence, the “epic” (narrative, nondramatic) theatre is based on detachment, on the Verfremdungseffekt (alienation effect), achieved through a number of devices that remind the spectator that he is being presented with a demonstration of human behaviour in scientific spirit rather than with an illusion of reality, in short, that the theatre is only a theatre and not the world itself.

In 1949 Brecht went to Berlin to help stage Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (with his wife, Helene Weigel, in the title part) at Reinhardt’s old Deutsches Theater in the Soviet sector. This led to formation of the Brechts’ own company, the Berliner Ensemble, and to permanent return to Berlin. Henceforward the Ensemble and the staging of his own plays had first claim on Brecht’s time. Often suspect in eastern Europe because of his unorthodox aesthetic theories and denigrated or boycotted in the West for his Communist opinions, he yet had a great triumph at the Paris Théâtre des Nations in 1955, and in the same year in Moscow he received a Stalin Peace Prize. He died of a heart attack in East Berlin the following year.

Brecht was, first, a superior poet, with a command of many styles and moods. As a playwright he was an intensive worker, a restless piecer-together of ideas not always his own (The Threepenny Opera is based on John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera, and Edward II on Marlowe), a sardonic humorist, and a man of rare musical and visual awareness; but he was often bad at creating living characters or at giving his plays tension and shape. As a producer he liked lightness, clarity, and firmly knotted narrative sequence; a perfectionist, he forced the German theatre, against its nature, to underplay. As a theoretician he made principles out of his preferences—and even out of his faults.

the information is given from:www.britannica.com.

Dante

Dante

Synopsis

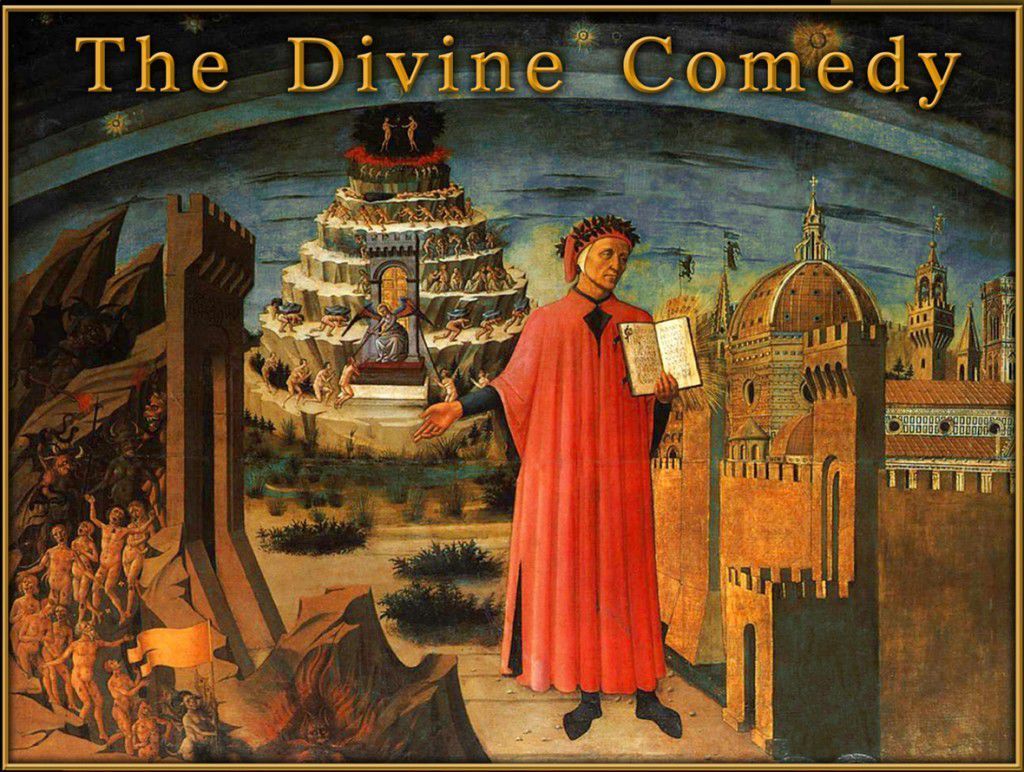

Dante was an Italian poet and moral philosopher best known for the epic poem The Divine Comedy, which comprises sections representing the three tiers of the Christian afterlife: purgatory, heaven, and hell. This poem, a great work of medieval literature and considered the greatest work of literature composed in Italian, is a philosophical Christian vision of mankind’s eternal fate. Dante is seen as the father of modern Italian, and his works have flourished since before his 1321 deathEarly Years

Dante Alighieri was born in 1265 to a family with a history of involvement in the complex Florentine political scene, and this setting would become a feature in his Inferno years later. Dante’s mother died only a few years after his birth, and when Dante was around 12 years old, it was arranged that he would marry Gemma Donati, the daughter of a family friend. Around 1285, the pair married, but Dante was in love with another woman—Beatrice Portinari, who would be a huge influence on Dante and whose character would form the backbone of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Dante met Beatrice when she was but nine years old, and he had apparently experienced love at first sight. The pair were acquainted for years, but Dante’s love for Beatrice was “courtly” (which could be called an expression of love and admiration, usually from afar) and unrequited. Beatrice died unexpectedly in 1290, and five years later Dante published Vita Nuova (The New Life), which details his tragic love for Beatrice. (Beyond being Dante’s first book of verse, The New Life is notable in that it was written in Italian, whereas most other works of the time appeared in Latin.)

Around the time of Beatrice’s death, Dante began to immerse himself in the study of philosophy and the machinations of the Florentine political scene. Florence was then was a tumultuous city, with factions representing the papacy and the empire continually at odds, and Dante held a number of important public posts. In 1302, however, he fell out of favor and was exiled for life by the leaders of the Black Guelphs (among them, Corso Donati, a distant relative of Dante’s wife), the political faction in power at the time and who were in league with Pope Boniface VIII. (The pope, as well as countless other figures from Florentine politics, finds a place in the hell that Dante creates in Inferno—and an extremely unpleasant one.) Dante may have been driven out of Florence, but this would be the beginning of his most productive artistic period.

Exile

In his exile, Dante traveled and wrote, conceiving The Divine Comedy, and he withdrew from all political activities. In 1304, he seems to have gone to Bologna, where he began his Latin treatise "De Vulgari Eloquentia" (“The Eloquent Vernacular”), in which he urged that courtly Italian, used for amatory writing, be enriched with aspects of every spoken dialect in order to establish Italian as a serious literary language. The created language would thus be one way to attempt to unify the divided Italian territories. The work was left unfinished, but it has been influential nonetheless.

In March 1306, Florentine exiles were expelled from Bologna, and by August, Dante ended up in Padua, but from this point Dante’s whereabouts are not known for sure for a few years. Reports place him in Paris at times between 1307 and 1309, but his visit to the city can’t be verified.

In 1308, Henry of Luxembourg was elected emperor as Henry VII. Full of optimism about the changes this election could bring to Italy (in effect, Henry VII could at last restore peace from his imperial throne while at the same time subordinate his spirituality to religious authority), Dante wrote his famous work on the monarchy, "De Monarchia,” in three books, in which he claims that the authority of the emperor is not dependent on the pope but descends upon him directly from God. However, Henry’s popularity faded quickly, and his enemies had gathered strength, threatening his ascension to the throne. These enemies, as Dante saw it, were members of the Florentine government, so Dante wrote a diatribe against them and was promptly included on a list of those permanently banned from the city. Around this time, he began writing his most famous work, The Divine Comedy.

The Divine Comedy

In the spring of 1312, Dante seems to have gone with the other exiles to meet up with the new emperor at Pisa (Henry’s rise was sustained, and he was named Holy Roman Emperor in 1312), but again, his exact whereabouts during this period are uncertain. By 1314, however, Dante had completed the Inferno, the segment of The Divine Comedy set in hell, and in 1317 he settled at Ravenna and there completed The Divine Comedy (soon before his death in 1321).

The Divine Comedy is an allegory of human life presented as a visionary trip through the Christian afterlife, written as a warning to a corrupt society to steer itself to the path of righteousness: "to remove those living in this life from the state of misery, and lead them to the state of felicity." The poem is written in the first person (from the poet’s perspective) and follows Dante's journey through the three Christian realms of the dead: hell, purgatory, and finally heaven. The Roman poet Virgil guides Dante through hell (Inferno) and purgatory (Purgatorio), while Beatrice guides him through heaven (Paradiso). The journey lasts from the night before Good Friday to the Wednesday after Easter in the spring of 1300 (placing it before Dante’s factual exile from Florence, which looms throughout the Inferno and serves as an undercurrent to the poet’s journey).

The structure of the three realms of the afterlife follows a common pattern of nine stages plus an additional, and paramount, tenth: nine circles of hell, followed by Lucifer’s level at the bottom; nine rings of purgatory, with the Garden of Eden at its peak; and the nine celestial bodies of heaven, followed by the empyrean (the highest stage of heaven, where God resides).

The poem is composed of 100 cantos, written in the measure known as terza rima (thus the divine number 3 appears in each part of the poem), which Dante modified from its popular form so that it might be regarded as his own invention.

Virgil guides Dante through hell and a phenomenal array of sinners in their various states, and Dante and Virgil stop along the way to speak with various characters. Each circle of hell is reserved for those who have committed specific sins, and Dante spares no artistic expense at creating the punishing landscape. For instance, in the ninth circle (reserved for those guilty of treachery), occupants are buried in ice up to their chins, chew on each other and are beyond redemption, damned eternally to their new fate. In the final circle, there is no one left to talk to (as Satan is buried to the waist in ice, weeping from his six eyes and chewing Judas, Cassius and Brutus, the three greatest traitors in history, by Dante’s accounting), and the duo moves on to purgatory.

In the Purgatorio, Virgil leads Dante in a long climb up the Mount of Purgatory, through seven levels of suffering and spiritual growth (an allegory for the seven deadly sins), before reaching the earthly paradise at the top. The poet’s journey here represents the Christian life, in which Dante must learn to reject the earthly paradise he sees for the heavenly one that awaits.

Beatrice, representing divine enlightenment, leads Dante through the Paradiso, up through the nine levels of the heavens (represented as various celestial spheres) to true paradise: the empyrean, where God resides. Along the way, Dante encounters those who on earth were giants of intellectualism, faith, justice and love, such as Thomas Aquinas, King Solomon and Dante’s own great-great-grandfather. In the final sphere, Dante comes face to face with God himself, who is represented as three concentric circles, which in turn represent the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The journey ends here with true heroic and spiritual fulfillment.

Legacy

Dante’s Divine Comedy has flourished for more than 650 years and has been considered a major work since Giovanni Boccaccio wrote a biography of Dante in 1373. (By 1400, at least 12 commentaries had already been written on the poem’s meaning and significance.) The work is a major part of the Western canon, and T.S. Eliot, who was greatly influenced by Dante, put Dante in a class with only one other poet of the modern world, Shakespeare, saying that they ”divide the modern world between them. There is no third.”