Be Golden as gold mine & Green as leaf

carpe diemBe Golden as gold mine & Green as leaf

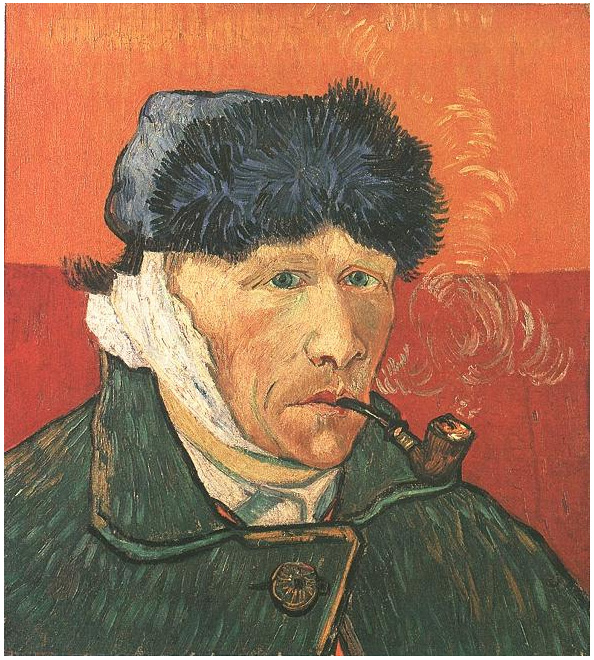

carpe diemVan Gogh’s Ear

Van Gogh’s Ear

Vincent van Gogh has become much more than just a painter. He has become the image of a “tortured artist.” His fame is due to his painting, of course, but it is his life that took him beyond a famous painter and made him a legend.

|

|

Outside of his paintings, when people think of van Gogh they think of his ear - or lack thereof.

In February 1888, Vincent moved to Arles to begin his dream of starting an artist colony, painting in the south of France in a more direct light. He loved the landscape, the light, and the people. The first step was finding a house and setting up a studio. He found that in a small yellow house on No. 2 Place Lamartine for 15 francs per month.

Part two of the plan was getting another painter to stay with him and paint. The previous year, in 1887, Paul Gauguin moved to Paris where he met Vincent. Vincent's brother Theo, an art dealer was representing Gauguin and introduced the two. Vincent respected Gauguin and thought him the perfect painter to join him in Arles. With some convincing from Theo, Gauguin agreed and arrived on October 23rd, meeting Vincent at the door of the yellow house early in the morning.

The painters got along well for weeks. They ate together, they drank together, and they painted together. In the small house they were together almost all of the time. Van Gogh and Gauguin both had an interest in Impressionism and painted the same subjects. They painted side by side, showing how two painters can show the same scene in different ways.

Arles was proving to be a productive place to paint for both artists, but Gauguin was moving away from Impressionism. Van Gogh, on the other hand, was producing some of his finest paintings – ones that would later be shown in the biggest museums in the world.

Things didn’t stay happy for long. Eventually Gauguin was finding it hard to live with Vincent. Gauguin felt that they had accomplished a lot, and that his views on art were becoming increasingly different than those of Vincent. This situation was becoming stressful to both men. At times Vincent still showed affection to Gauguin, but at others he detested him.

By December, Gauguin was thinking about leaving. He wrote to another painter “I’m staying for now, but I’m poised to leave at any moment.” Finally, on December 23rd, Vincent asked Gauguin if he was planning to leave. When Gauguin said yes, Vincent was devastated. He tore out a sentence from a newspaper, stating simply “The Murderer took flight” and handed it to Gauguin. After supper Gauguin left the house to go for a walk. Barely out of the yellow house, he heard the footsteps of Vincent approaching. When he turned to look, he saw Vincent walking towards him with a razor in his hand. Vincent stopped, put his head down, and quickly returned home.

The details of the rest of the evening are sparse, as van Gogh often awoke after his times of “madness” with little recollection of the previous events. From what we can gather from accounts from Gauguin, the police, and his brother Theo, Vincent returned home while Gauguin stayed in a hotel. Later that night, after 10:00 P.M., Vincent took a razor and cut off a portion of his left ear. The police would find blood all over the house, with blood soaked rags in the studio and bloody handprints along the wall leading upstairs. Vincent took the ear and wrapped it in newspaper. With a hat pulled down over his wound, he, with ear in hand, left the house to go to a “maison de tolerance”, a brothel close to the house. There he asked for a girl named Rachel who he gave the ear to saying “Guard this object carefully.”

The next night when Gauguin woke up and started to return to the yellow house he saw the police in front with a crowd of onlookers surrounding. When the police found Vincent in his bed, covered in blood, they initially thought he was dead, perhaps by suicide. Gauguin felt the body and discovered that Van Gogh was still alive. He asked the police to wake him gently, and if Vincent asks for Gauguin, to say that he had returned to Paris. Vincent was taken to a hospital to recover, where he continuously requested to see or talk to his friend Gauguin. He still thought his friendship could be salvaged, and he was already planning new paintings.

It seems an odd and harsh reaction for Vincent to cut off his ear. But Vincent van Gogh was deeply troubled and his mind made connections that appear mad. More than anything Vincent wanted the situation to work. He wanted a place where artists lived together, painted, talked about painting, and learned from each other. Van Gogh felt his idea was happening with the arrival of Gauguin. And then, he knew that he ruined it. He blamed himself for not being able to get along with Gauguin. Just as with past relationships, this too fell apart.

Vincent may have felt he deserved to be punished for ruining another friendship and dream, and his mind would immediately race to find connections. His religious past could bring up thoughts of Peter cutting off the ear of a Roman soldier after Judas betrayed Christ. There was a popular book at the time where a character was punished by having his ear cut off, and a month earlier Jack the Ripper cut off the ear of a woman. We don’t know how Vincent’s mind worked, but it is possible that he saw a pattern of punishment and saw a way to punish himself.

Scientists Now Know Why People Scream

Scientists Now Know Why People Scream

A baby wails upon an airplane's liftoff, a person shrieks when he stumbles upon something shocking, a kid throws a tantrum because she wants to get her way—people scream in reaction to all kinds of situations.

But exactly why we scream has remained a mystery. Now, new research published in the journal Current Biology suggests that hearing a scream may activate the brain's fear circuitry, acting as a cautionary signal.

Scream science is a new area of study, so David Poeppel, a professor of psychology and neural science at New York University, and his co-authors collected an array of screams from YouTube, films and 19 volunteer screamers who screamed in a lab sound booth. (This last collection method, by the way, was a highlight for Poeppel, who said he found listening to and judging screams an amusing break from the monotony of lab work.)

The researchers first measured the sound properties of screams versus normal conversation. They measured the scream's volume and looked at how volunteers responded behaviorally to screams. They then looked at brain images of people listening to screams and saw something they found fascinating—screams weren't being interpreted by the brain the way normal sounds were.

Normally, your brain takes a sound you hear and delivers it to a section of your brain dedicated to making sense of these sounds: What is the gender of the speaker? Their age? Their tone?

Screams, however, don't seem to follow that route. Instead, the team discovered that screams are sent from the ear to the amygdala, the brain's fear processing warehouse, says Poeppel.

"In brain imaging parts of the experiment, screams activate the fear circuitry of the brain," he says. "The amygdala is a nucleus in the brain especially sensitive to information about fear." That means screams are inherently considered not just sound but a trigger for heightened awareness.

From these screams, Poeppel and his team mapped "roughness," an acoustic description for how fast a sound changes in loudness. While normal speech modulates between 4 and 5 Hz in sound variation, screams spike between 30 and 150 Hz. The higher the sound variation, the more terrifying the scream is perceived.

Poeppel and his team had volunteers listen to different alarm sounds and found people responded to alarms with similar variations: The more the alarms varied at higher rates, the more terrifying they were judged to be.

That huge variation in scream roughness is a clue to how our brains process danger sounds, Poeppel says. Screaming serves not only to convey danger but also to induce fear in the listener and heighten awareness for both screamer and listener to respond to their environment.